When my personal cutting boards began to show their age this fall I began to search for good replacements. After talking to my wife about my research she asked why I would want to buy cutting boards when I’ve engraved so many wooden ones for friends and family! This got me thinking about what a perfect cutting board would be to me and began a project that spiraled out of control and ultimately became the first Burks Builds product.

Requirements

To me the most important aspects of a cutting board are:

- Does not dull knives

- Dishwasher safe

- Food safe

- Does not slide on the countertop while in use

Everything else, including aesthetics, is secondary.

Material Selection

Some people care a lot about the food safety implications of gouges in a cutting board trapping food or bacteria, and claim that certain woods are inherently antimicrobial because of the way they draw moisture away from the surface. That may be true, but all wooden cutting boards need to be hand washed and dried which is something I am way too lazy to do myself.

Coating a wooden cutting board with some kind of epoxy or resin is a common way to make them dishwasher safe, but then you loose out on all of the benefits of a wooden cutting board except the looks. Another downside is that a thin external layer of plastic or epoxy is more likely to chip off from a knife cut and get into your food (“food safe” is not the same as “edible”!)

Plastic cutting boards are the other common option and they are dishwasher safe. I have been using a set of plastic cutting boards for 5 years and over that time they have warped slightly, accumulated stains, and built up a dense collection of gouges in the middle. There are a wide variety of plastics used in cutting boards that span a wide range of hardness and flexibility. Plastic cutting ‘mats’ are probably my favorite style because they tend to grip well and not hold knife marks. The mats meet all of my primary requirements, but like all other plastic cutting boards they cannot be laser marked.

Glass and slate cutting boards are an interesting category, and they do look very cool when laser marked. However, they are way too hard to use with a knife and would destroy a sharp edge almost instantly.

The final material I considered is paper composite (common trade names “Richlite” and “Paperstone“). This material is sold in sheets and is made from layered paper and epoxy, cured under pressure. It is a common material for countertops and even fancy cutting boards because of its food-safe rating and knife-safe hardness. Because the material is about 2/3 paper it “chars” when marked with a laser and retains a rich, dark coloration. However, because the rest of the material is essentially epoxy it can withstand temperatures as high as 350F making it dishwasher safe. The only downside is that 1/4″ thick sheets cost nearly $20/sqft!

While laser markings are not appropriate on the work surface of any cutting board (because the charred colored marking is not food safe and could get worked into the food while cutting) they can be a fantastic addition to the back side of a cutting board for when it is used for serving. Laser marking the Richlite seemed like a great way to personalize the cutting boards, and while plenty of people do this with black and white text and images I was unable to find anyone on the internet who had managed a halftone laser image marking on Richlite. With that knowledge my mind was made up: I was going to figure out how to do half tone laser marking on Richlite and then decorate the back of some cutting boards.

Cutting Board Build

Richlite sheets are sold directly in a few different sheet sizes and color options. I picked up a 2ft x 2ft x 1/4in sheet each of the basic ‘Natural’ color and the darker ‘R50’ color.

Design

My goal was to get two large and two small cutting boards out of each sheet so I stuck with a mostly rectangular board design to maximize my usage of the expensive material.

The large board is roughly 12in x 16in and the small board is roughly 8in x 12in. I put a silicone grommet in each corner to act as a “foot” and keep the board in place (silicone has a higher temperature rating than common rubber grommets, although silicone is much more expensive). I added a channel along the outside to catch juice and drippings which is a feature I enjoyed about my previous cutting boards (I mostly copied the width and depth of the channel from them).

CAM

I used Solidworks CAM to generate the toolpaths for my CNC router. It was my first big project with this CAM software and it took some getting used to. In the end I think I ended up with a good enough set of paths and parameters, although I am still not happy with some of the start/stop points as well as the total number of passes in the slot cutting operation (something about my cleanup pass requirements?)

The general machining strategy is to start by cutting the channel, then cut the four corner holes, then finish by cutting out the perimeter. I will be using woodworking tape to adhere the Richlite to the spoil board and then cut through the entire perimeter (without tabs) to free the part from the work.

Testing

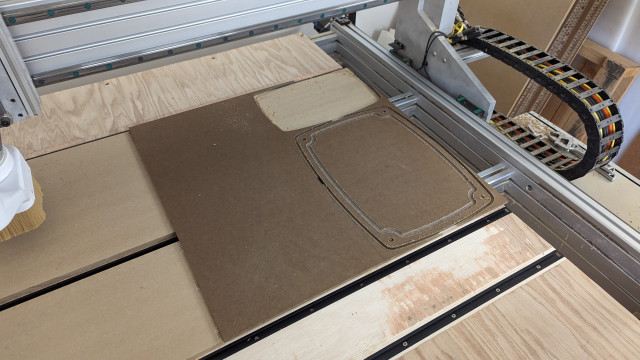

I started with a few dry runs of the GCode and everything seemed fine. However, I wanted to test the entire process on something much cheaper than my precious Richlite. I used some 1/4″ oak plywood leftover from the large clock build and cut it to match a 2ft x 2ft Richlite sheet.

I learned a few things from this test that I was able to transfer to the final cut program:

- I needed more tape around the small cutting boards to keep it secured

- The channel didn’t seem quite large enough so I opted to increase it for the final product

- The bottom layer of plywood was still connected along the profile cut in some places, so I extended the depth of the cut even further past the bottom of the stock to ensure complete separation in the future

- The bullnose bit I was using to cut the channels plunged into the material better than I expected, so I opted to use it for the holes and profile cut too (instead of a straight endmill) to avoid a tool change

- The woodworking tape looses its grip over time (days) so it is best to commit to doing the project all at once without letting it sit on the machine idle

Machining

I started by flattening the spoil board with my fly cutter to make sure I had a good surface for the tape to adhere to. This was probably unnecessary, but I altered the perimeter geometry of the boards slightly after the test and wanted to avoid any problems related to cutting near, but not directly on, previous gaps in the spoil board.

Next I laid out the tape on the spoil board, increasing the density compared to the test part. In hindsight I should have only increased the density on the top and cut the two small boards there while leaving the tape more sparse on the bottom where the big boards would be cut.

I laid the first Richlite sheet on the tape, being careful to keep it square to the table because I only had 1/4″ of stock available on all sides. Then I climbed up on the table and stood on the stock, walking over the tape seams to make sure it was well adhered.

I then laid out a center mark with a pencil for each cutting board. This let me eyeball the X/Y center point with the endmill before running each program. The Z position was set using a piece of paper to check when the tool contacted the board (because I still haven’t set up my touch probe…)

I ran the small cutting board in the top right corner and the large cutting board in the bottom right corner. The boards came out well!

The material seemed to cut a lot more like plastic than wood, which meant that the finish didn’t require much cleanup at all. It also meant that there were real “chips” instead of a ton of sawdust which made cleanup easier. The large board was run with the vacuum boot and it did a great job of sucking away all of the chips.

The holes in the corners came out well, despite only being slightly larger than the endmill.

Finishing

I cleaned up the outside perimeter and the holes with a deburr tool, then used 240 grit sandpaper to manage the fuzz on the channel. The grommets fit really well into the holes and I tested to ensure that the board did not slide around on the counter.

I laid out a snack on the first board and tried it out – perfect! I repeated the whole process on the lighter “Natural” color sheet with no changes. Now I have 8 cutting boards to work with!

Laser Marking

The cutting boards are great on their own, but what drew me to this project was the opportunity to laser mark the back of the cutting boards.

Initial Testing

I began using the scraps as test pieces to try out different laser engraving settings for halftone marking. On the darker material this process seemed completely futile. My normal “test strip”, a linear discrete scale of grey colors, kept turning out as a nearly monochromatic patch.

I tried so many different power settings, density settings, lenses, and brightness pre-scaling techniques. In the end I found that there are two main complications when engraving Richlite:

- The initial marking is extremely dark and pure, but when you wash away the soot the remaining marks are duller and less well defined

- Starting with a darker background (especially with the R50 material) does not leave much room for shades of grey to be visible

- The laser made a very small pinpoint dark mark, but left a ring of discolored material around the dark mark, which is difficult for the half tone algorithm to compensate for

For comparison, here is an uncleaned scale (bottom) next to a cleaned scale (top) with similar settings:

I eventually gave up on halftone marking (at least for the dark color) and worked on how to do monochrome marking.

Monochrome

The biggest issue with the monochrome marking was avoiding tiny visible horizontal lines of less-burnt material between every row.

Normally I use between 0.2mm and 0.1mm scan intervals with the 2 inch lens, but I ended up needing to use a 0.05mm scan interval to ensure a consistent darkened surface.

Power settings were another difficult factor to dial in. Too much power and the engraving went too deep, which makes it harder to clean, but too little power meant a less visible image. Using a dense scan interval also meant that I was using a higher resolution image, which started to cause timing issues when the laser reversed direction. Luckily there is a setting (“Reversing offset” in RDWorks) to compensate for this. Eventually I found my sweet spot and committed to some settings for the cutting boards.

In the end I used these settings on my 55W CO2 laser to get crisp, dark, detailed monochrome images marked on Richlite with minimal depth of cut:

- 2″ Focal distance lens, properly focused

- 350mm/s raster speed with 0.15mm reversing offset

- 20% Power (11W)

- 508 DPI image resolution with 0.05mm raster scan interval

These settings worked really well on the darker R50 Richlite, but also on the lighter Natural color Richlite. Thin dark lines were able to “pop” very clearly which allowed me to use very intricate designs (like the floral patterns shown below). Large filled areas had a consistent non-grainy color and texture which worked well for other simpler designs.

Halftone

I resumed my halftone testing, this time on the lighter material, with a few ideas on how to make it work better. My first problem to solve was getting the laser marked dots to have a consistent color, even if it meant a bigger dot. By playing with power settings and laser timing (very slow raster speeds so the laser has time to fully come up to power for each pixel individually) I was able to improve the quality of the dot created by the laser. At the same time I was messing around with dot density (DPI) and size (lens focal length) to see how the bleed from the dots changed the overall “color” of the resulting image.

Once I had the power settings dialed in I started trying to increase my resolution (DPI) so that lighter greyscale colors could still be distinguished based on different dot densities. 254 DPI was about as far as I could push it, and with that density I really had to slow down the raster speed to ensure that the dots did not show up as dashes.

I was still fighting the issue that after about 25% fill the apparent darkness of the halftone color didn’t appear to change much.

There appeared to be a lot of available “contrast” in the 0-25% range so I started to work on adjusting the images to scale their brightness into that range. I used an area of the test photograph I had in mind to check the results after each iteration on a scrap of Richlite. The test image had extremely dark and extremely bright areas, as well as small details with both contrasting and non-contrasting backgrounds.

I taped the rest of my scraps together to run one final large scale test. It was generally successful, but I learned that very bright areas (like my wife’s forehead and white shirt) can get very weird patterns when the dots are too sparse.

I put in a minimum darkness of about 3% and it seemed to fix the problem in the RDWorks preview. With that final change I took a deep breath and ran the program on an actual cutting board.

The results were better than I expected. Nothing beats the crispness of the uncleaned image, but the final result was still very satisfying even after cleaning. Details like the glasses frame and my shirt pattern came out great, but I wish the necklace would have turned out a bit better.

The final settings that I used for halftone marking were:

- 1.5″ focal distance lens, properly focused

- 60mm/s raster speed with no reversing offset

- 14% Power (7.7W)

- 254 DPI image resolution with 0.1mm raster scan interval

- GIMP level adjustment of 10.0 and output limit of 246

In the future I may consider using some kind of clear sealant on the halftone image so that I can trap the initial crisp, sooty image straight off the laser. my biggest concern is finding a food-safe coating that won’t yellow after dozens of cycles through the dishwasher.

This was a very interesting project and I am happy with my replacement cutting boards! I am hoping to get some more feedback from the laser community to see if there is anything else I can do to improve my halftone quality in Richlite, but until then I am satisfied with my current process. I think this is a unique enough creation that it is worth offering for sale to others, so I created Smith Mountain Make, an online store to sell these cutting boards and a few other worthwhile projects.